My local paper recently published a series of articles lamenting Nova Scotian P-12 students’ performance on standardized math and literacy tests. At issue, reported author Frances Willick, is the use of modern teaching techniques such as “whole-language” learning for teaching reading and “discovery-based” learning for teaching math.

My local paper recently published a series of articles lamenting Nova Scotian P-12 students’ performance on standardized math and literacy tests. At issue, reported author Frances Willick, is the use of modern teaching techniques such as “whole-language” learning for teaching reading and “discovery-based” learning for teaching math.

Willick’s sources, such as Mount Saint Vincent University (MSVU) education professor Jamie Metsala, say these modern methods have failed kids. Teachers should focus more on traditional techniques like phonics for teaching reading, and repetitive drills for teaching basic math.

All of us should welcome robust public debates on pedagogical techniques, and most of us in the education world do. After all, we want to do the best job we can at educating our kids.

Unfortunately, “crisis” articles like these are not very helpful. First, they sensationalize what is actually happening in our classrooms; and second, they ignore the political context of what is happening in our education system.

Back to Basics?

Let’s look first at the debate on teaching reading, with the caveat that I am not a literacy expert (although high school teachers do still work on literacy skills, directly and indirectly).

Two methods of reading instruction have been used in North American schools over the past several decades. The phonics method consists of teaching letters and syllables as building blocks, which kids learn to “sound out” and use to make words. In contrast, in the whole-language method, the emphasis is on learning whole words and recognizing them in context, analogous to the way children learn to speak.

According to MSVU’s Jamie Metsala, curriculum in Nova Scotia is tilted too far towards whole-language. Metsala says kids need more drilling on simple sounds and syllables in order to make them proficient readers. Phonics instruction is indeed present in classrooms in Nova Scotia, but Metsala says it isn’t enough, and points to standardized test scores which she says show too many students aren’t reading at grade level. (Let’s forget for the time being the question of how much standardized test scores actually tell us about the health of an education system.)

The reading debate isn’t new. This article from 1997 details how heated a political issue it became in California in the early 1990’s, to the point where it influenced a state election.

Willick’s article cites research supporting the conclusion that phonics is the best way to teach literacy. However, plenty of other research on the “Reading Wars” disagrees, saying phonics instruction is no silver bullet. In fact, one of the major reports cited by Willick in support of phonics instruction – the comprehensive (U.S.) National Reading Panel of 2000 – is by no means as unequivocal a defense of phonics as her article presents. For example, it states that phonics instruction “fail[s] to exert a significant impact on the reading performance of low-achieving readers in 2nd through 6th grades.”

A similar, equally protracted debate exists in mathematics education. Recently, “discovery math” came under fire in Alberta from those advocating a “back-to-basics” approach. A parent started a petition demanding that Alberta get rid of its new math approach, claiming that modern teaching methods confuse kids and demanding more drills on things like multiplication tables. Parents even rallied at the provincial legislature. Here in Nova Scotia, Willick reports that some in the world of math education are concerned about Alberta’s curriculum being imported here.

“Back to basics” can be an attractive rallying cry, not least because of its simplicity and appeal to nostalgia. But like many seemingly simple solutions to complex problems, it’s often misguided.

It’s worth noting, first of all, that schools in the real world generally use a combination of traditional and modern teaching techniques. This piece by Jonathan Teghtmeyer of the Alberta Teachers’ Association argues that the so-called math crisis is a fiction, and that old-fashioned drills are still an important strategy used in the math classroom among others. In the wake of the media storm in Alberta several other active classroom teachers also wrote defenses of modern teaching techniques, though by my (non-systematic) observations they didn’t get the same press coverage as the back-to-basics crowd. In response to concerns about discovery-based learning here, the Nova Scotia Department of Education told the the Herald this province would use a “balanced approach between back-to-basics and discovery-style instruction.”

Pedagogy and politics

It’s important to appreciate that these seemingly technical debates have political and philosophical dimensions. To begin to understand how, consider this excerpt from Alberta teacher and writer Joe Bower’s blog on the “math wars”:

“I still remember being taught how to divide fractions in junior high. I was told to flip the second fraction and then multiply. It was a trick that enabled me to get high scores on the tests.

Here’s the problem…

To this day, I have absolutely no idea why I flip the second fraction and multiply. I have no idea what the mathematical reasoning is. I can get the right answer on the test, but there is nothing mathematical about my (lack of) understanding for dividing fractions. If we want to confuse and turn students off of math, I can think of no better strategy than to make math a ventriloquist act where children are merely told the most efficient ways of getting the right answer. This is mindless math mimicry.”

Education debates aren’t just about how we teach; they’re about why we teach what we do. What kind of a society do we hope to create and sustain through our public education system? Is it a better world than the one we live in now? Are people in it happy?

The answers are reflected in the status we assign to certain academic subjects, but also in how we conceive of the acts of teaching and learning themselves. Modern pedagogical methods like discovery-based math and whole-language reading attempt to look beyond simple mechanics of words and mathematical algorithms and answer questions like: why are we teaching this, anyway? What message does the way we do it send to kids? How can we make them enjoy learning?

“Back to basics” is, by and large, a conservative movement: it assumes that the “old way” of doing things worked just fine. It seems to ignore, however, that so many people quite disliked their own school experience precisely because of traditional schooling’s rote-learning, this-is-for-your-own-good-so-suffer-through-it mentality.

Modern pedagogy has attempted (albeit not always successfully) to teach things we think kids need to know, while still helping them foster motivation and desire for learning – arguably an inherent trait in humans.

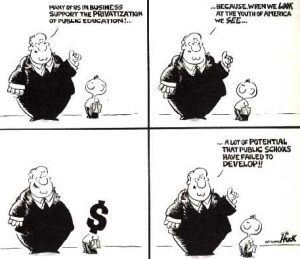

Looking at who supports the back-to-basics movement is instructive. A good example is the Ontario-based Society for Quality Education (SQE), which counts among its board of directors a range of business-types, a former senior officer of the National Citizens’ Coalition (once directed by Stephen Harper) and no one with any apparent on-the-ground experience in public education. The SQE says public schools have a “bias towards progressivism” and “child-centred learning” (horrors!) and trumpets the Mike Harris government of 1995-2003 as a successful model of school reform. The Society is funded by conservative foundations such as the Atlas Economic Research Foundation, and they recently sponsored Florida governor Jeb Bush’s speech at the Economic Club of Canada.

One “honorary patron” of the SQE is Paul Bennett, a frequent media commentator on educational issues here in Nova Scotia. Bennett, a veteran of elite private schools like Toronto’s Upper Canada College, now works as an educational consultant and regularly authors reports for the Atlantic Institute for Market Studies, the leading right-wing think-tank on Canada’s East Coast. Bennett rails against teacher unions at every opportunity and promotes market-oriented reforms as the solution to perceived educational problems. He and I occasionally debate things on Twitter, and he often uses the word “progressive” as an insult. (For the record, I occasionally agree with things he says.)

Alignment with business interests doesn’t necessarily mean a pedagogical technique is always bad, and just about any teacher (including me) uses them sometimes. But it’s worth looking at how Willick’s stories fit with a narrative common in media reports of public education for some time now. It goes like this: public schools are failing at educating kids. They’re too expensive, and they don’t produce “results” that the job market wants. Therefore, we need to cut “inefficiencies” in the system. And who runs things efficiently? Why, the private sector, of course! The kids in the Chronicle-Herald articles are not getting the attention they need in public school, so they turn to private tutoring companies, which are portrayed as the ones doing things right. To be clear, these companies are doing nothing wrong, but their context is very different to that of a public school – students or parents self-select, and they are not subject to fluctuations in government funding.

This is the same narrative which has led “charter schools” – private schools that receive public money and are not subject to all the same curricular and regulatory constraints as public schools – to “compete” with traditional public schools in many parts of the U.S.

There are, of course, lots of reasons why schools are different from businesses, and the free-market logic pushed by the business crowd is fallacious when it comes to schooling. In the U.S., while some charters seem to perform about as well as traditional public schools in terms of their test scores and graduation rates, many others perform worse. This is despite the fact that most charters can choose which students to admit, meaning public schools are left with disproportionate numbers of high-needs students. Lack of regulatory oversight means that charters have faced controversy on everything from questionable disciplinary practices to high-level corruption.

(As if on cue, this past weekend the Chronicle-Herald published a baseless screed calling for charter schools in this province.)

By no means do public schools get everything right, and we should constantly aim to improve them. But setting up straw men that undermine the very notion of public education helps no one. Society’s expectations of its public education system have changed dramatically in the last century – we know much more about student special needs and mental health issues, and we expect all students to graduate high school, for example – yet we act surprised that costs to education has gone up and that educators seem overworked and unhappy. Improving education goes hand in hand with solving other problems such as economic inequality and systemic racism (and to the Chronicle-Herald’s credit, the final story in its series on Nova Scotia schools examines the very real effects of poverty on student learning).

When we’re told the education system is broken, we should pay attention to who’s telling us, and who stands to benefit from the “fixes.”

Hi Ben,

I enjoyed your blog post and the perspective it brought to issues surrounding teaching and learning in Nova Scotia.

I’d like to offer you some of my insights into the writing of The Chronicle Herald’s recent series on math and reading education in Nova Scotia.

I don’t think the articles are lobbying for “back to basics” education. The point of the article on reading isn’t that we need to abandon all other techniques and focus exclusively on phonics; it’s that phonics/phonological awareness are tools that aren’t being used enough in the classroom. The article states clearly that a balanced approach is needed — exactly what you’ve mentioned in your own article.

The math article avoids coming down on one side or the other of the discovery vs. back to basics battle. I don’t think that’s a terribly useful battle, so I really tried to steer clear of seeming to laud one or the other. As with reading, most seem to agree that including teaching techniques from various camps is essential. The people interviewed in my article hold a variety of opinions — sometimes contradictory ones — and make what I think are good points about both sides. The article was not a rallying cry for discovery or back-to-basics math, but rather an exploration of some issues in math education.

After the first two articles came out, I received some criticism from readers — mostly other private tutoring companies who were not mentioned in the articles — that the articles “promoted” the companies. The reason I wanted to include the voices of private tutors is not that I think they’re necessarily “doing it right.” When some kids aren’t able to learn in the public system, they turn to private companies to get what they’re missing. So, tutors are the ones who see and work with students whom the public system is failing in specific areas. They know what deficiencies exist in the public system because they see the fallout. I think that’s a pretty important perspective to include.

Whenever I write articles that examine the public education system and point out areas of deficiency, I hear from readers who suggest that I’m undermining public education. In my view, I am simply bringing forward concerns about the system, often with the hope that this will spur debate and put pressure on authorities to do better. And that’s a good thing. It’s not meant to attack the essential and valuable work that takes place in our education system. If anything, it’s meant to bolster it by encouraging improvement.

I deliberately avoided deeming the reading and math scores a “crisis.” I simply pointed to an ongoing, longstanding problem that I felt was worthy of further investigation. If 20-30% of kids are chronically failing, to me, that’s a problem. Media often get accused of “sensationalizing” issues. I fail to see how my stories sensationalize these issues, or how these issues are “straw men,” as you suggest. They are not trying to shock or scare anyone; they are simply drawing attention to a real problem.

While I know that standardized tests are controversial, the fact is that they remain one of the only publicly available measurements of the success of our education system, flawed though they may be.

One final note: I was disappointed that I wasn’t able to write the third story myself on how socioeconomic status can affect education. I ran out of time to work on this before the series ran, but I was insistent that we include a story that examined that part of the equation.

Thanks for the ongoing conversation, Ben.

Cheers,

Frances

Hi Frances,

Thanks for taking the time to read this piece and respond. I disagree with your assessment that your pieces are “balanced.” The subtitle of your first piece is “Techniques such as phonics can reverse a disturbing trend toward poor reading skills.” Your main sources of information are Jamie Metsala and tutors/families who have benefited from phonics instruction. You cite a comprehensive study (The National Reading Panel) which, when I looked it up, was found to be actually much more nuanced and problematic than your piece suggests.

The “other side” of this debate would have involved interviewing someone with knowledge of whole-language instruction, or at least giving it serious consideration. Someone I respect said to me once: “I don’t want to teach a kid to read if he’s going to hate reading for his whole life.” We can debate the merits of philosophies like that, but they’re not even given any consideration. There’s no mention at all as to why a technique like whole-language was ever used in the first place.

I agree that your math piece is more balanced, but I still find it lacking. Again the subtitle here points to some experts’ worries about discovery math, which is really the premise for the whole piece. The “balance” comes in towards the end.

You say you avoid characterizing the issue as a crisis, but really all you avoid is using that word, especially in the literacy piece. It’s all well and good of you to say you understand standardized testing only gives us limited information, but then we have two front-page pieces based on the premise that we should be alarmed about the results. I’m not disagreeing that we should try to improve literacy and math skills in the province, but these tests are always held up as the problems the public should be alarmed about. Have you seen the OECD PISA letter, where hundreds of educators have decried the effect the PISA scores are having on the way we discuss education in the public sphere? http://oecdpisaletter.org/ Are we going to see any articles in the Herald about kids’ declining civic literacy (as indicated by declining voter turnout and participation), or environmental illiteracy, or knowledge of Aboriginal issues, or health, or access to the arts?

My biggest qualm, though, is that the articles don’t take into account their political context. Even if one agrees that your articles are balanced, in the past few weeks the Herald has run (off the top of my head): an editorial calling for back-to-basics, an op-ed by Jamie Metsala, and pieces by Ralph Surette and Ian Thompson making simplistic right-wing arguments that the province spends too much money on public education, that the private sector should get involved, and that we should run schools more like businesses. Paul Bennett has a regular column in the Herald. Your pieces fit their narrative perfectly, whether or not you intended it. The only voices published that counter this narrative tend to be when I or a colleague has a moment to write an op-ed.

I’m glad the piece about poverty ran as well. But I worry about its effect, coupled with the other two. The corporate ed-reform movement in the U.S. has used a lot of social-justice rhetoric – we need to “improve education” for poorer students, etc. The result tends to be that (some) less affluent kids spend hours getting drilled in “the basics” while more affluent kids get a rich, varied curriculum with arts, phys ed, etc. That makes me uncomfortable.

I don’t think you intend to undermine public education at all, or that you are on one “side” or another of the education privatization debates. But I do think these pieces unfortunately bolster the narrative of the side that already has much more access to the media to propagate its ideas.

Thanks for engaging and looking forward to reading more of your work,

Ben

Where I teach (public Ontario ) every year the powers that be send us to in-service sessions to learn/try another new way to teach something…..we never get a chance to perfect any of these “ways” we just keep getting MORE things to do. As elementary teachers we are generalists and the majority of us must teach all subjects. It is very difficult to become proficient in so many things without experience. To me one solution to this is subject specialists. However, this is shot down because “studies say” that would mean too many teachers for the students to experience. People who understand their subject area have the skills and the passion to teach it. A few last thoughts, balance indeed……take away the hoops that teachers have to jump through…..parents let your students do their own work and stop saving them and making excuses…..cut the cord! It’s NOT broken it just has too many pieces and we need time to the puzzle together.

I’m interested in the math debates. One comment is that it seems this “back to basics” approach is appealing to an “education market” where nostalgic parents are consumers. In my opinion at least, going back to the basics with math will not prepare students for the “markets” they will confront in the future – or better yet to make a positive social contribution in the future by using math.

We seem to confuse math with arithmetic. Joe Bower draws the distinction between “mindless math mimicry” and understanding math as a language. If we really want success in so-called math-based, high-tech industries people need to understand math as a language much more. This is what helps you construct an economic model, a climate system model, or become an engineer, or computer scientist, or wall street speculator (the latter is not the most useful profession, but it is where lots of our mathematical talent resides).

In my mind the “market oriented” reforms to education contain a contradiction in that they are likely to miss out on a type of education that is more likely to create a workforce with more “human capital”. Of course education should be more about much more than just preparing people for the market. I’m just point out the contradiction between the education market and the labour market that I perceive from reading your analysis and my own personal opinions on the “math wars”.

If people learn to like math and use it to its full advantage there are many things that can be done with it. I wish I learned “why” we were doing math instead of just plugging in formulas.

As an educator, I see both sides of the spectrum. Yes we need kids to understand the WHY of the math, and grok it more than just the rote memorization of the past. But as a sub who occasionally goes into math classes (while not being a math educator by training) I also see kids struggle mightily with the “whole math”. As someone who struggled with math, it was the tips and tricks I discovered that GOT ME THROUGH. Some kids need these “flip the last fraction to divide” because otherwise they are just going to keep struggling, and then shut down. When I show them the trick, you can literally see the light go on. Yes math and english should be more (as a Geography trained educator, we have gone away from just memorizing capitals and rivers and oceans and I don’t think you will ever see that come back as the primary means of teaching geography and social studies, and most Soc.St. teachers I know couldn’t be happier) that memorization, but at the end of the day, sometimes you just need to know, in a pinch, what 8×7 is.

Enjoying the conversation… I teach grade 7-12 math. I maintain that half of my job is teaching math; the other half is teaching kids that they can both like and do math. Lots of emotional energy is needed in this teaching field, and lots of damage control efforts to pick up the pieces of haunted pasts. But I would mostly love to find a good resource that answers thoroughly, with real life examples, the famous question, “When am I ever going to use this stuff?” I have heard several quaint teacher responses, but I’d like help with putting together a 2-4 hour workshop to put my students through at the beginning of the year. I think we have succeeded in persuading society in general the value of reading skills. I don’t think we’ve arrived when it comes to mathematics.

Huge problem with standardized testing: Teachers teach to pass the test not to learn. My high school math teacher went to grade them, just so that he would know how they’re scored for the next year.

The tests compare how well you prepared for the test, not how much you know. My school was very small. It had limited resources, and the students suffer for it. Even the top 1% is about the top 10% at any other. The students didn’t pick where to live. They also count for way too much of your grade.